PalmOS: A Nine-year waste of Time and Money

Editor’s note: This was originally published on March 16, 2008.

Back in 1999, someone showed me an early Palm Pilot PDA. I was hooked immediately and bought my own a few days later.

In those days, a Palm PDA was had a lot of deficiencies. Memory was limited to about 8MB, the screen was a paltry 160×160, and switching between programs was slow and cumbersome. But it was worth it for the novelty of having a touch screen computer small enough to fit in a pocket.

Some years later I had given up carrying my Palm in favor of a cell phone. Then I heard about the Treo, and picked myself up a Treo 600. Having a PDA and a phone together was the right idea, and the possibilities of an internet-connected Palm platform seemed endless. I even installed Palm’s development environment with the intention of building a side career as a Palm applications developer.

Now, the Treo 600 was fun for a little while, but it didn’t take long for reality to sink in. The camera was too crude to take any kind of worthwhile picture. The screen, though color, was still only 160×160. Memory was now only 24MB, and the applications were old and familiar — not in a warm way but in a way that makes you wonder what they’d been doing for the past five years.

Writing Palm applications was a shocking revelation. If you wrote Windows code in the Windows 3.1 days, you’ll be right at home writing code for Palm OS because Palm is every bit as crippled and clunky as 16-bit Windows running on top of DOS. Make one pointer mistake and you trash not just your own application but the whole device — I did it more than once, and I’m a very careful programmer. And that 24 meg of memory? Sure, you can insert a memory card with 1G or more, but the extra memory doesn’t become part of the OS like main memory. In a program, you have to look for it and address it specifically if you want to use it, not unlike the way old DOS programs had to use expanded memory APIs to address memory beyond 640K.

The worst thing about my Treo 600 was that people frequently complained that they couldn’t hear me over a loud buzzing noise. This turned out to be a common problem that people had to solve for themselves by disassembling the handset and twisting a pair of wires. Unbelievable.

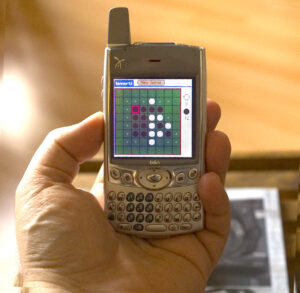

I bought a new Treo in 2007, but it’s only marginally better than the first one. The screen and the camera are a little better. The memory situation, the applications, and the programming tools are much the same. The web browser stinks, third-party apps are of varying quality, and the whole thing is just too slow. Often it locks up or crashes when I’m trying to do something basic like answer a call.

Watching the Palm devices evolve is like watching the PC revolution in slow motion. What PCs gain in a year takes the Palm people a decade.

In the meantime, Apple has given us a phone with a real computer in it — and a user interface that genuinely makes sense. When I use a Treo to browse the web, I expect it not to work at all; if I manage to get what I need, some 15 minutes of waiting and carefully reading Palm’s idea of an “optimized” web display later, I feel a deep sense of having pulled off something remarkable. With an iPhone it just works.

I hate being wrong, and I hate seeing so much work go down the drain, but it’s time to be honest about it: Palm is over. With a ten-year head start, Palm could have owned the mobile market, but they squandered their advantage. Mobile is now Apple’s game, and while I may wax nostalgic for my Palm Pilots and Treos of the past, you can bet that Palm isn’t getting any more of my mindshare or my money.

Epilogue: I remain an enthusiastic iPhone user and iOS app developer to this day.